Political News

Latest Videos

1:56

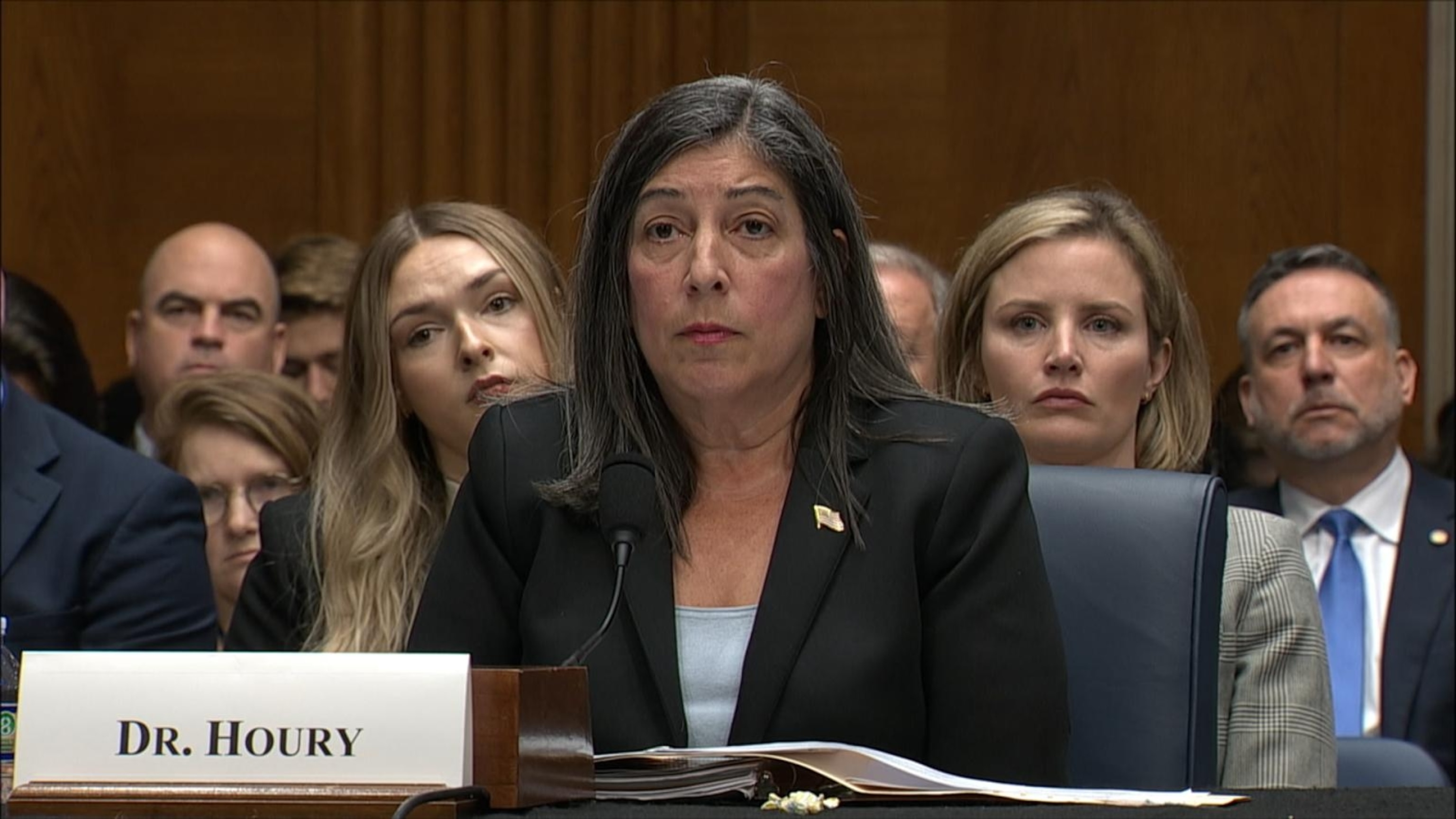

DC leaders debate crime in contentious House hearing

- 3 hours ago

0:33

Trump asks SCOTUS to let him remove Lisa Cook from Fed Reserve

- 7 hours ago

2:53

Kamala Harris wrote Buttigieg was top choice for running mate: The Atlantic

- 7 hours ago

5:02

Trump says he'll seek to designate antifa as 'major terrorist organization'

- 7 hours ago

9:35

Trump, Starmer hold news conference after signing science, tech partnership

- 8 hours ago

1:06

Charlie Kirk had 'good shot' of being president one day, Trump says

- 9 hours ago

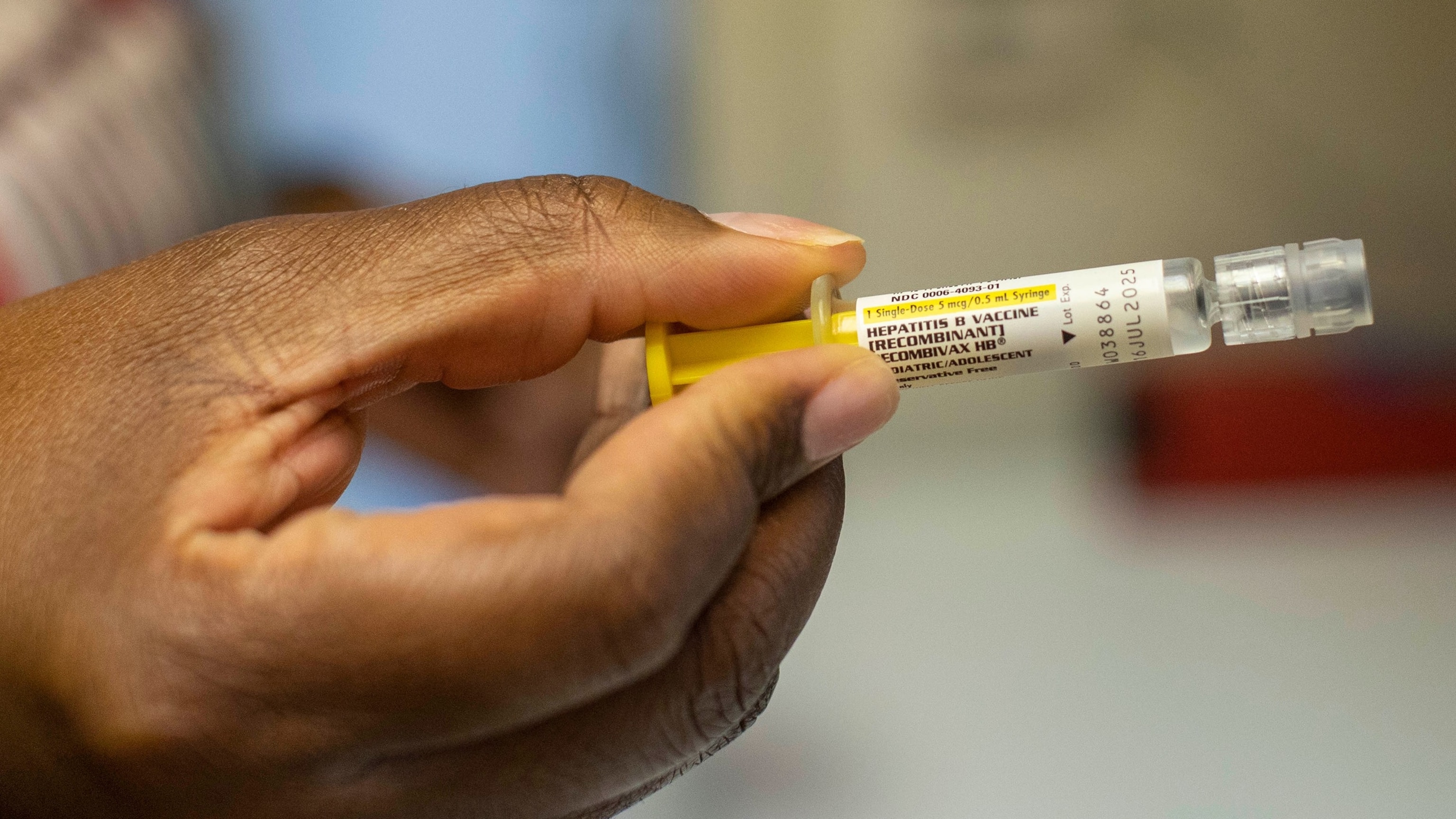

3:34

RFK Jr. said 'changes' coming to childhood vaccine schedule, according to Monarez

- 1 day ago

5:55

CDC has 'leadership vacuum': Former deputy director

- 1 day ago

5:19

Trump greeted by king, thousands of protesters in UK visit

- 1 day ago

6:07

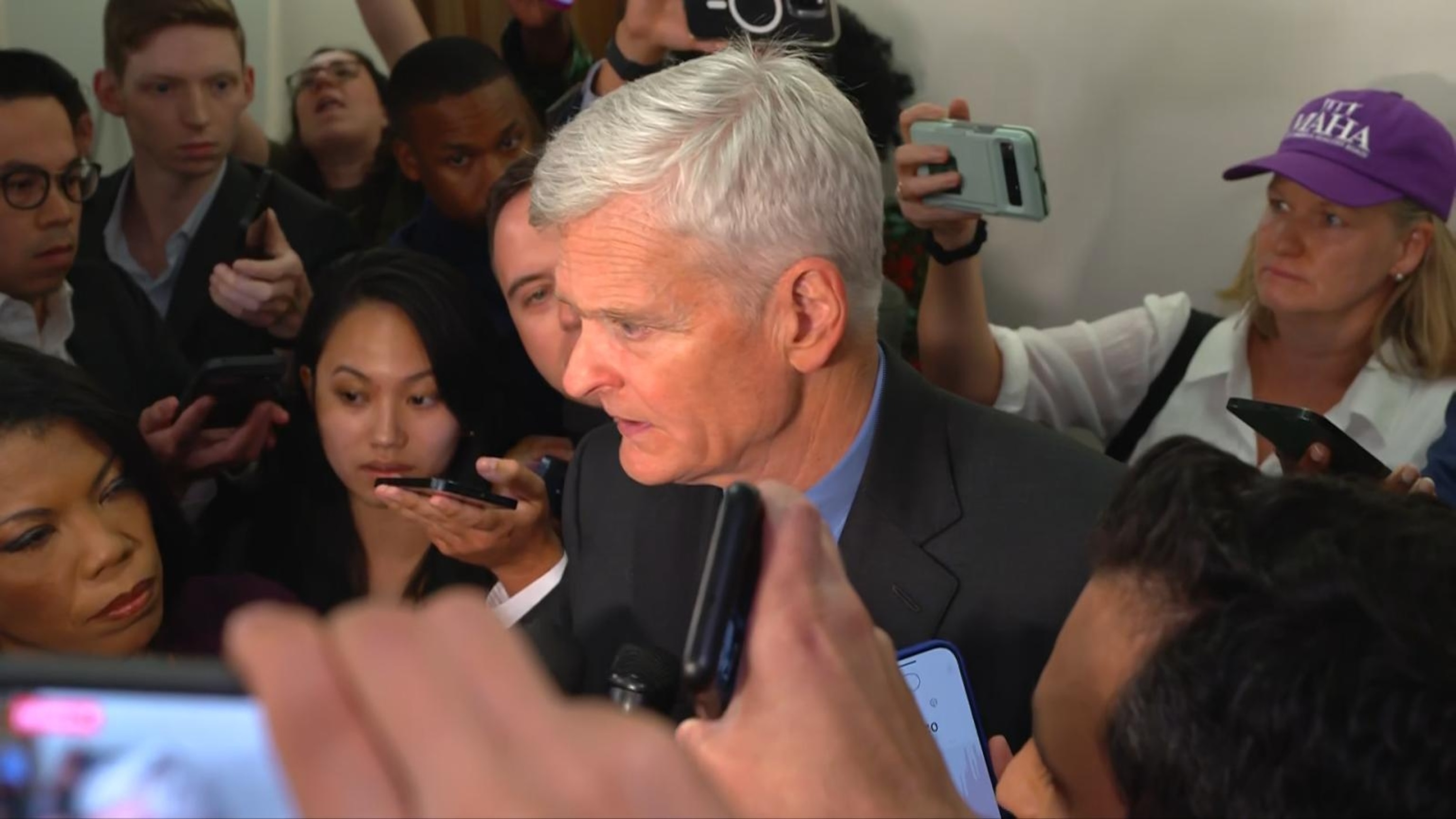

Sen. Bill Cassidy speaks after fired CDC director's hearing

- 1 day ago

Playlist · 10 Videos